|

Persian classical musician Kourosh Taghavi embraces a passionate approach to music that has impacted audiences around the world. His collaborative projects with master musicians and local cultural organizations work to fulfill his lifelong dream to promote Persian classical music. More recently, his ongoing efforts with the Center for World Music bring the setar and Iranian culture to San Diego school districts through hands-on instruction in Persian classical music. |

By Amanda Kelly

Persian classical music boasts a rich and unique history that juggles multiple identities: religious and secular, traditional and modern. Much like the history of Iran itself. Persian classical musician, Kourosh Taghavi, compares the style of music to reading a book. "It is a very contemplative form of music, if you will," he says. "It is not the sort of music one would want to turn on while vacuuming the floors or washing the dishes, rather it is the sort of music in which one would want to be fully immersed within in order to fully appreciate it."

Kourosh describes his entry into Persian classical music as a whim of sheer coincidence. He first came to the United States in 1984 to escape a dangerous political climate in Iran. While Kourosh was raised in an artistic environment that was infused with Iranian poetry, painting and calligraphy, music was never a significant part of his education. In fact, Kourosh was studying a microbiology textbook at a UCLA library when he decided medicine was not his path. "I would just take somebody else's place who really wanted to do [medicine,] so I put all my books in my backpack, zipped it, threw it in the garbage can and walked out of the library," he says.

The political climate in Iran during the early eighties was turbulent and even life-threatening for politically active citizens at odds with the changing government. Kourosh departed the country when he was seventeen. A few months after Kourosh had left his science books behind, he was in Santa Monica where two major figures in Persian classical music were touring: Mohammad Reza Lotfi and Hossein Alizadeh. It was the first series of Persian classical music concerts held after the Iranian Revolution, and Kourosh attended not knowing that he was about to discover his true calling.

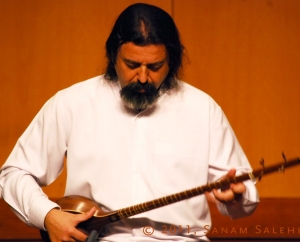

Mohammad Reza Lotfi was from Kourosh's hometown of Gorgan in Iran. Kourosh knew Lotfi was an influential figure in Persian classical music, but their paths had never crossed. At the moment Mohammad Reza Lotfi emerged on the stage and put his fingers to the strings of the setar, Kourosh realized he wanted to learn music. The quiet sonority of the long-necked lute and acumen of the musician plucking its strings had him captivated. Mohammad Reza Lotfi would eventually become a lifelong mentor and friend. "I decided then that I had to put everything else aside and start studying music," he says.

Traditionally when young musicians decide to pursue Persian classical music, they must seek out the wisdom and experience of a master musician. While sitting before the teacher, a novice musician listens as the teacher plays and learns to mimic what he or she sees and hears. However, in an oral tradition, it is not simply the music a student must observe. Kourosh says that a student must also consider the master musician's expressions and understandings of Iranian culture and literature. "It is a very holistic approach to music instead of just notation and sounds," he says. "Your daily life is so attached to your music and your music is so attached to your daily life they are almost inseparable." From the beginning, the teacher mentors technique, theory, approach and expression that help to form a particular ethos that relates directly to the history and experience of the master musician. In this regard, Kourosh learned to play the setar in the traditional way.

Learning music in such a holistic manner helps form a unique identity for the Persian classical musician. The performance style of musicians relates directly to the unique lineage under which they were taught. It is rather like a grammar that the musician learns from his or her master musician, building on that idea that the music is similar to reading a book. Over the past nine to ten centuries variations of the musical grammar of Persian classical music have developed through these teacher to student successions of thought, style and techniques. These specific musical legacies that embrace a repertoire are known as the Radif that "consist of systems and small melodies you're supposed to memorize note by note," but ultimately the goal is to move beyond the grammar of the Radif. Kourosh explains, "Obviously you can't forget it, but you need to detach yourself from it [the Radif] in order to tell your own story." Persian music is typically performed in small ensembles. It differs from other Middle Eastern musical styles in that it is rhythmically and melodically reflects Persian poetry. Few cultures worldwide appreciate poetry as much as Persian culture does.

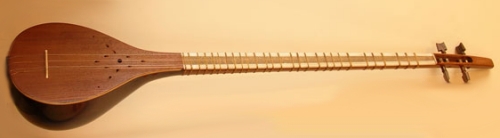

Kourosh says, "If I compose something or if I'm improvising something, I improvise and compose within that grammar that I've learned." The grammar serves as a foundation upon which the musician may build in a performance. Kourosh believes the setar has a privileged place in Persian music explaining that the setar differentiates Persian classical music from similar-sounding styles performed in Central Asia. The setar is the mechanism by which the Persian classical musician navigates the grammar of the Radif. An average-sized setar is roughly 3 feet long, 8 inches wide, with a deep gourd-shaped soundbox. Its strings are plucked with the nail of the index finger. Because of its soft sonority it has been considered an instrument of solitude and for this reason the setar is the preferred instrument of Sufi mystics.

Persian classical music enables its listeners to embark on a journey through the rich history of Persian culture as well as their own individual thoughts and feelings. Kourosh's teacher said to him that a musician and his audience are separate only at the beginning of a performance. Once the music begins, the two merge on an inward journey to experience the history and language of Persian classical music. "I like to tell my audiences this is the culture I'm coming from; this is the culture I like to share with everybody else," says Kourosh.

Un Setar Persa

The Center for World Music facilitates the connection between schools and artist-teachers through its World Music in the Schools program. In the last two years, the Center for World Music has had 20 artist-teachers placed in residencies and four other individuals who present special school assemblies or fund-raising events. Executive Director of the Center for World Music Monica Emery says, "As an organization, we do our best to represent as many different cultures from around the world as possible. We aim to bring students opportunities they may otherwise never have. Learning to play the setar is one of those very rare experiences we can offer. But our school program is not just about music and dance, it also introduces young people to cultures outside of their own." Kourosh's position an artist-teacher with the Center for World Music enables him to spread further awareness of Persian culture and music to elementary school students (grades 3rd-6th) in San Diego. He is currently finishing a residency at Del Mar Heights Elementary and will continue every other week at Bird Rock Elementary until April or May.

Kourosh begins his classes by introducing basic rhythms and melodies to students. With this foundation he can eventually introduce rhythms and melodies indigenous to Persian classical music. The Center for World Music has purchased setars that students may practice on and learn the music. "I try to teach them everything I think is worthy for a child to learn through music," he says.

Beyond the elementary classroom, Kourosh is one of the founding members of Goosheh, Seda and Namad Ensembles with which he has toured throughout Europe, Asia and the US. His collaborations with renowned artists such as Hossein Omouni and Robert Bly as well as with cultural organizations like San Diego Museum of Art only further demonstrate his lifelong effort to promote Persian classical music. He has taught the Radiff as a faculty member at San Diego State University and he continues to offer traditional one-on-one instruction for students. Kourosh hopes that at some point, if the topic of Iran or Persian culture is brought up later in their lives, his students will not think of images on the news, but that they will fondly recall the long-haired guy with an earring that taught them Persian classical music. He also hopes that connection will inspire a change for good in the world.