Washington Elementary School

Andy Asaro grew up in Little Italy when it was a tight-knit community of fishermen, 6000 families strong. In 1959 he left for a tour of duty in Naples, Italy. When he returned three years later, he looked around and asked himself, "What happened to the neighborhood?"

"It was like the neighborhood was abandoned," recalls Lou Palestini, another area native. "There was no more hustle and bustle. You could stand on the corner of Fir and India Streets and shoot a cannon either way and not hit a soul." India, the main thoroughfare, had been a major focus of community life.

Washington Elementary School, a sacred institution that had been attended by successive generations of Italian-American children, took a big hit.

"Everybody went to that school from my mother's age on. It was the center of a lot of community activities," Asaro says. The building, constructed in 1915, "always reminded me of the White House with its pillars and stairs," says Palestini, one of its former students. "It had a gym downstairs, a big playing field, which is all freeway now. They took all that away."

Asaro, a retired schoolteacher who lives in the modest bungalow he grew up in, reminisces about the community of his youth. "When I grew up, we had a lot of space. There were empty lots. We used to hang out by the bay a lot because everybody was a fisherman."

Sunday mornings were a favorite time. "You would walk down the street and everybody was cooking sauce and meatballs, a little differently, but everybody was doing the same thing. The big meal was at noontime."

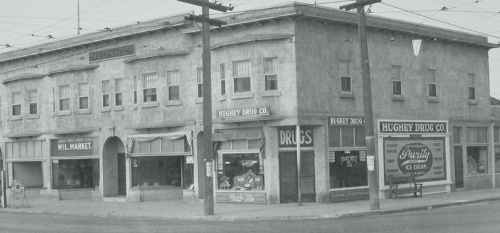

The Bay City Drugstore at the corner of India and Grape, now a camera shop, housed an old fashioned soda fountain that attracted the neighborhood kids. Adults, too, found the drugstore an inviting place to gather and socialize.

"All the guys would hang out on that corner. When I would come out of the house, all of the older guys were across the street. It was a comfort zone," Palestini recalls.

"This was our world. We went to school, we went to church, we played on the playgrounds."

Tuna Fisherman

|

The Italian section of San Diego had been a self contained, self-sufficient neighborhood for decades. From West Laurel to Ash and from First Avenue to the bay, residents were walking distance from grocery stores, bakeries, restaurants, a butcher shop, doctors, a Catholic church, an elementary school, a drugstore, fire department, bars, and even a massage parlor. |

Hughey Drug Store

John Rippo's maternal grandparents were among the early settlers. They arrived on a steamship from San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake along with other homeless Italians, having lost everything.

"They built tents and shacks and little houses out of whatever they could find all along India Street," Rippo says.

San Diego's fledgling Italian community was not entirely welcome in its new home, Rippo says. His grandfather told this story:

One rainy evening shortly after arriving, native inhabitants thought to be local Ku Klux Klan visited the settlers. His grandfather, eighteen years old at the time, joined with other men in a nighttime brawl that resulted in the death of at least two Klansmen.

"The Americans were buried face down at the crossroads of India and either Fir or Date. In Catholicism, that's a great insult," Rippo says. "The end result was that the Americans never came back."

Bayside Community Center

In the ensuing decades, the Italian population became firmly rooted in San Diego, growing into a prosperous working class community. The men went out on boats for months at a time while the women stayed home to care for the family or work in one of the city's three tuna packing plants.

For a while, the Italian section became known for producing another popular product: wine. During Prohibition, people were allowed to produce up to fifty gallons of wine a year for personal consumption and sacramental use.

"Everybody made wine and everybody sold it," Rippo says.

"The police, the judges, the lawyers and the major players in San Diego would show up in limousines to buy their booze from Italians on India Street - even as they were prosecuting them for rum running and bootlegging."

Giacalone Family

What happened to the Italian section? The Crosstown Freeway (I-5), constructed as part of a national effort to expand the nation's freeway system.

"Most of the neighborhood got really quiet because it eliminated a lot of people," Asaro says.

There had been a big debate about where to put the I-5 freeway, whether to take a coastal route or go inland. "They decided on inland rather than on the coast," Asaro says.

"The freeway went straight through Little Italy," says Palestini. "But the downtown portion of it avoided impacting businesses. We felt slighted on the deal

By the early 1980's, Little Italy had lost so much of its ethnic character that it was no longer referred to as Little Italy. Efforts to make it a tourist attraction to fit in with downtown redevelopment plans began around this time, but it wasn't until the Little Italy Association (LIA) was founded in 1996 that the area started to come to life in a big way.

"We were dead. We weren't even Little Italy, we were Midtown," Danny Macero, vice president of the LIA says. "The Little Italy Association brought it back to be officially called Little Italy."

Masquerade at Festa

The LIA is a non profit organization representing the interests of the businesses and residents of Little Italy. Over nearly twenty years, it has had a dramatic impact on the neighborhood, rescuing it from obscurity and transforming it into one of San Diego's most popular destinations.

The LIA accomplished this through funds from the Little Italy Maintenance Assessment District (MAD), the Little Italy Business Improvement District (BID), the Little Italy Parking District, and various other programs. The organization makes sure that roads and sidewalks are repaired and maintained, and it funds improvements such as the Piazza Basilone, Amici Park, the Little Italy sign arching over India Street and banners proclaiming notable Italian-Americans such as Danny Kaye, Joe DiMaggio and Martin Scorsese.

Had an organization as savvy, well funded and influential as the LIA existed sixty years ago, there might not be a freeway running through Little Italy today.

The LIA oversees the development of Little Italy, setting ground rules, maintaining order and planning for the future. Anything that goes on in Little Italy is vetted through the LIA first.

Festa

"We don't want another Gaslamp," Macero says. "We want it safe. We take care of everything, so it's a safe place to be, guaranteed." The LIA website proclaims the new Little Italy "A Hip & Historic Urban Neighborhood."

Asaro and other long time residents lament the changes to the neighborhood they grew up in. "Instead of a neighborhood, now it's a destination. I knew the neighborhood would change, but not to this extent," Asaro says.

Walk through Little Italy and you can still find remnants of the neighborhood it once was - the occasional bungalow lurking ghost-like between multi story condominiums and trendy restaurants. You see a couple of them across from Filippi's Pizza Grotto, a few grouped together at Hawthorne and India Street, and the house Asaro still lives in, on India between Hawthorne and Ivy.

The structures are modest, tidy and out of place with the evolving character of the area. Their diminishing presence serves as a reminder that the lives of several thousand families, long a vital part of San Diego's cultural and economic life, were uprooted to make way for a steel and concrete thoroughfare.

On India Street, you can see LIA's latest addition to Little Italy, a large-scale development at the corner of Date Street. Previously the site of the Reader building and DeFalco's, a supermarket only old-timers would remember, this is the future Piazza Famiglia, Plaza of the Family, modeled after the great piazzas of Italy. When completed, it will see the block of Date Street between India and Columbia turned into a pedestrian walkway bordered on both sides by upscale shops and housing.

In addition to its physical transformation, Little Italy, with the support and encouragement of the LIA, has become a locus for events and activities related to Italian culture, food and art. The Saturday Mercato is San Diego

Chalk Drawing at Festa

Part of LIA's charter is to honor the Little Italy of the past as it guides it into the future. But tributes to the past seem few and far between. There is a painting on India St. called "i pescatori," The Fishermen, depicting a boatful of men reeling in their catches on a rollicking sea. Other than that, little among the chic restaurants and shiny condominiums is reminiscent of the neighborhood's original working class character.

"I grant you there's a few pockets of the old neighborhood here, but it's going away," says Palistini, who serves as treasurer on the LIA board.

"I think we owe it to the neighborhood, to the immigrants who came and settled here, to have some kind of heritage center" similar to one in Point Loma commemorating the Portuguese who, like the Italians, earned a living from the sea.

"But the commitment I am looking for is not there yet."

Understandably there exists a tension between the elderly former residents who remember what Little Italy once was and the people who created and enjoy what Little Italy has become. A vibrant residential community is now a robust commercial district where Italian culture has become a commodity or cultural production that brings many visitors to the area for entertainment, Italian cuisine and cultural events. Compared to what it was several decades ago, Little Italy is far more enjoyable for visitors looking for an Italian experience, but the cultural loss is nevertheless quite real. Perhaps a heritage center longed for by Palistini would be a fitting tribute to the hardworking and committed Italian immigrants who established an entire industry in San Diego.

By Tony Rocco

All photos courtesy of the Little Italy Association of San Diego